Book Review

The Man Who Died Twice

The life and adventures of Morrison of Peking

By Peter Thompson and Robert Macklin

Allen and Unwin, 380 pp, $32.95

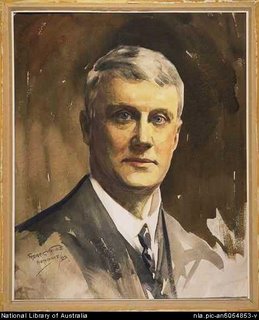

Morrison of Peking became a model for Australian correspondents abroad. He was brave, handsome, resourceful and ultimately a celebrity. But there was more to Morrison than media hype. Like many other heroes of Victorian era journalism, he was also a racist, an agent of colonialism and quite possibly a British spy.

Through his influential reporting, George Morrison helped shape British and Australian views of what he described as an exotic and dangerous "Orient". Morrison was the first eminent Australian journalist in Asia, whose personality sometimes seemed bigger news than the stories he covered. If he lived today, he might be offered a job on Sixty Minutes.

The most recent biography about Morrison, The Man Who Died Twice (Allen&Unwin) has rather a lot about his admirable qualities. But it finds precious little to criticise or even to identify his darker side. This new book is not unique here. The Man Who Died Twice joins a string of boys own accounts of Morrison, ranging back through Australian literature, penned by writers as diverse as Banjo Paterson and Frank Clune.

In many ways Morrison was a stereotypical journalist. Contemporary correspondents might recognise Morrison's sometimes prickly relations with editors who changed his copy, his concern with expenses and his "complex and varied relations" with government officials. (Tiffin, 1978, 11/15) More significantly, Morrison shared many contemporary Australian journalists' ambivalent attitude to Asia, admiring Western constructs of "Oriental" culture, while sternly critical of perceived failings, such as corruption and violence.

Morrison the adventurer

Trained as a medical doctor, Morrison was without doubt a courageous and pioneering journalist. His 5,000 kilometre journey across China in 1894 and his resulting catalogue of impressions and experiences, An Australian in China, established his international reputation as an eyewitness reporter. He subsequently served for 17 years as The Times correspondent in China.

He was not a great writer but rather a competent reporter and an excellent analyst. The editor of his letters, Lo Hui-Min, said that while Morrison lacked confidence in his own writing style, he had virtues which it was said other foreign correspondents failed to achieve:

If he lacked any stylistic power, it was more than compensated for by the conviction which his plain and lucid narrative inspired in his readers; his style was the more masterful because it was apparently flat. However, this impression came less from his style than from his whole attitude. His adventures prove his courage, but even there he was not reckless, and he was not an adventurer in journalism; he was keen to have a 'scoop', but was never sensational. (Lo Hui Minh, pp 3/4)

Morrison was regarded by many of his contemporaries as the leading authority on the Orient. A.B. (Banjo) Paterson met him "by great good luck" in 1901 when on a visit to Hong Kong. "It was an education to listen to him, for he spoke with the self confidence of genius," Paterson later wrote. "With Morrison, it was not a matter of 'I think'; it was a case of 'I know'". (Paterson 1992 pp 122/123) Paterson admired Morrison's system of contacts which delivered exclusive reports on international treaties days before they were even signed by the nations involved:

Dr Morrison lives for the most part in Peking, where he is in touch with the best informed Chinese circles. But he moves constantly about, travelling in men-of-war, on tramp steamers, on mule litters, on pony back, or on his feet, as occasion demands. He is a powerful, wiry man, of solid and imposing appearance, and those who know him best in China, say that he has mastered the secret of all Chinese diplomacy - bluff. In China, you must save your face, e.g., preserve your dignity at all hazards. He never allows any Chinaman to assume for a moment that he (the Chinaman) is in any way the equal of the Times correspondent in China.

(IBID p129)

Paterson clearly approved of Morrison assuming superiority over "the Chinaman". But viewed a century later, Morrison's work can be seen as written unashamedly from the perspective of a British imperialist. Morrison, it might be remembered, was an Australian by birth who called himself an Englishman. Indeed, according to Philip Knightley, at times Dr Morrison was little better than an agent of the British government. Knightley claimed that while presenting himself as a private individual, Dr Morrison "had gone off on a special mission for the Foreign Office through the still independent Asian nations of Burma, China, and Siam, pretending he had nothing to do with either the newspaper or the British government". (Knightley 1975 p 61)

Morrison corresponded privately with senior British officials, and identified passionately with British interests "We all feel very grateful to The Times for the way it has championed British interests out here." he wrote from Peking to Ethel Bell ( the wife of the proprietor) on 14.3.1899. (Lo Hui-Min , p 116)

Morrison was a man of contradictions. He an imperialist who advocated Britains’s civilising role. Yet he was aware of European ignorance about the "Orient" and contemptuous of the resulting failure of many Western missionaries. He openly admired the achievements of the millenniums-old Chinese civilisation.

Morrison as myth

Morrison the man was becoming a myth. Author and correspondent, Frank Clune claimed that Morrison's "sentiment of sympathy for non-Europeans was at variance with the hates, fears, phobias, complexes and dislikes of his fellow Australians, which culminated in the White Australia policy". Clune even said that Morrison was "without prejudice of race or colour":

Earnest by name and earnest by nature, he [Morrison] had discovered the great truth that colour is only skin deep; that pigmentation of the hide of a kanaka, a Moor, a Jamaican negro, or an Aryan is only a surface disguise for the character of the man beneath.(Clune 1941, 1941)

During the 1940’s Clune had himself been Australia’s best selling non-fiction writer. A former Anzac digger, Clune set himself squarely in the forefront of a series of books about adventurous travel in the Orient. In preparing his book on "Chinese" Morrison, Clune appeared at the Tokyo office of the Society for International Cultural Relations and demanded "everything [the society] had on Morrison". In characteristically high handed dealings with Orientals, Clune further ordered that the books be sent to his Sydney home . Yet in spite of this research, Clune appeared to be rather selective in what he reported. Contrary to what Clune wrote, Morrison, was most definitely not invulnerable to 19th century Australian prejudices about Asians. To be precise, he had a xenophobic fear of Chinese immigration:

We cannot compete with Chinese; we cannot intermix or marry with them; they are aliens in language, thought and customs; they are working animals of low grade but great vitality. The Chinese is temperate, frugal, hardworking, and law evading, if not law abiding - we all acknowledge that. He can outwork an Englishman and starve him out of the country - no one can deny that. To compete successfully with a Chinaman, the artisan or labourer of our own flesh and blood would require to be downgraded to a mere mechanical beast of labour, unable to support wife or family, toiling seven days in the week, with no amusements, enjoyments, or comforts of any kind, no interest in the country, contributing no share to the expense of government, living on food that he would now reject with loathing, crowded with his fellows ten or fifteen in a room that he would not now live in alone, except with repugnance. Admitted freely into Australia, the Chinese would starve out the Englishman, in accordance with the law of currency - that of two currencies in a country, the baser will always supplant the better. (Morrison p224/225)

Morrison was a racist who saw Asian males as potential sexual predators. To Morrison, Asians were "animals" and "beasts", with whom there must be no miscegenation. "Our own flesh and blood", in this case, the British race, must be protected from the "baser" currency who would starve out the white man. Morrison may have been subsequently portrayed as a dispassionate observer of Asian events. But he saw himself as an outsider in Asia; a spokesman for Western ideas and intentions. Ultimately. to Morrison, Asians were "working animals of low grade" fit only to be servants to the intellectually superior white man.

Morrison as imperial icon

The Man who died twice, by journalists Peter Thompson and Robert Macklin, is described in its cover notes as “a powerful and gripping biography of an Australian journalist and adventurer who paused only to tell his stories and plan his next foray among the great events and leading figures of his day.”

The title refers to Morrison’s prematurely reported death during the Boxer uprising. In 1900, Morrison distinguished himself by fighting on the side of colonial powers at the outbreak of the uprising; an indigenous rebellion against the dismemberment of China, the introduction of foreign culture and the imposition of foreign economic control. Times correspondents did not have journalistic immunity in colonial wars. Morrison would have been aware of the fate of an earlier Times Special correspondent to China, Thomas Bowlby, who was seized, tortured and killed by Chinese forces near the end of the Second Opium War in 1860. (Beeching, ,1975, p 299)

On 16 July 1900, the London Daily Mail carried a story datelined Shanghai, which claimed that Dr Morrison had died in a desperate last stand at the besieged British legation at Beijing. In a report resonant of Kipling and the 19th century adventure novel, the defenders were said to have hurled back wave after wave of Chinese assault troops until their ammunition ran out. The legation guards were allegedly wiped out to the last man and everyone else, Morrison included, was "put to the sword in the most atrocious manner". It should be noted that the report while filed by a special correspondent in China, came from Shanghai: isolated from Beijing by almost a thousand kilometres of Chinese countryside populated by largely hostile peasants, roving bands of fanatical Boxers and several well trained Chinese Imperial armies. (O’Connor p 177/178)

The story was entirely false.

Nevertheless, the massacre report was picked up and reprinted by many other newspapers. As a result, the next day The London Times carried a glowing obituary for Morrison, claiming that it would be foolish or unmanly to doubt the awful "truth". According to the Times, no newspaper had "a more devoted, a more fearless and more able servant than Dr Morrison". In the editorial the Times said:

His last message was dated June 14 th, just before the legations were finally cut off from the outside world. It was an ominous message. One shudders to think of the awful days and nights that were to follow, waiting for the help that never came, before the tragedy was finally consummated and the last heroic remnants of Western civilisation in the doomed city were engulfed beneath the overwhelming flood of Asiatic barbarism. (Cited by Clune 1939 p 296)

Such press reports, while generating enormous public sympathy for Morrison as a British hero, also mobilised support for European military intervention in China. The report was part of the self justifying mythology of Empire, setting Morrison among Imperial icons like the British women murdered by rebellious Indian sepoys at Cawnpore during what the British called the Indian Mutiny. The Forbidden City in Beijing was indeed "doomed"; it was shortly after sacked by the avenging forces of "Western civilisation". Morrison disapproved of the excesses of the occupying Europeans, particularly the Germans. But this didn’t stop him from benefiting from the looting, a fact glossed over by The Man who died Twice. (Thompson/Macklin p 200) who described it as souveniring.

While alarmist stories of Asiatic violence and savagery might fuel the fires of imperialism, the embarrassingly wrong report of Morrison’s death offended the notions of accuracy held by the great metropolitan newspapers. As an apology, the Manager of the Times, C.F. Moberley Bell wrote to Morrison:

The extent to which we have been bamboozled both as to your safety and as to your danger, by the lying Chinese would I think surprise even you. . . . I am sorry to say however, that the English press has been as bad or worse. That they should be deceived - as we ourselves were - is natural but I am afraid that half of the telegrams were deliberately faked in Fleet Street. (Lo Hui-Min pp141/142)

Getting bamboozled about the truth

The authors of The Man who died Twice saw Morrison as “a noble professional” who might serve as beacon for the rising generations in journalism. They lamented that, “ the struggle for truth against vested interests has never been more desperate”. Morrison not only made history, they wrote. He also made it.

But for whom?

Morrison was neither the first, nor the last Victorian journalist to act in the narrative of Empire.

In the 19th century, it was not unusual for feted reporters to be regaled for the best sellers they wrote about their scrapes in the colonial wars they supported. One of the then best known, but now largely forgotten of Morrison’s predecessors, “Bokhara” Burnes wrote a book about his journey to Afghanistan , which made him too the toast of British society. He secretly wrote political and military reports for which he received a Knighthood. Like Morrison, Burnes later found himself trapped by an indigenous uprising, in this case Kabul at the beginning of the first Afghan war. Burnes was less lucky than Morrison however, being hacked to pieces by the mob and having his severed parts hung up in the Kabul market, thus prematurely ending a promising career in journalism, espionage and diplomacy. There were many others. Winston Churchill was a Boer war correspondent who was rather more successful in mixing writing, politics and Empire.

Morrison’s record, as the authors admit, was not perfect. But neither should be seen as “an icon of inspiration”; a role model for contemporary journalists. Morrison was a man of many parts, not all of them recommended to modern society. Cyril Pearl, the author of Morrison of Peking (Penguin 1967) was closer to the money when he described Morrison as “a latter day Elizabethan who never grew up”. “He was infected with the raging Imperialism of the nineties [1890s] , that curious conspiracy of rogues and idealists, poets and entrepreneurs, prophets and profit seekers, which he saw romantically as a crusade,” Pearl wrote. (Pearl 1967)

Selected Bibliography

Clune, Frank. 1939. Sky High to Shanghai. Sydney. Angus and Robertson.

Clune, Frank. 1941. Chinese Morrison. Melbourne. The Bread and Cheese Club

Beeching, Jack. 1975 The Chinese Opium Wars , London: Hutchinson.

Lo Hui-Min. 1976. The Correspondence of G.E. Morrison. London : Cambridge University Press.

Morrison, G.E..1985 An Australian in China : Being the narrative of a quiet journey across China to Burma. London. Oxford University Press.

O'Connor, Richard.1973.The Spirit Soldiers : A Historical Narrative of the Boxer Rebellion. New York. G.P. Puttnam's Sons.

Paterson, Banjo. 1992 "Happy Dispatches". Clement Semmler (Ed.) A.B. 'Banjo' Paterson; Bush Ballads, poems, stories and journalism, , 122/123.

Pearl, Cyril. 1970. Morrison of Peking. Middlesex. Penguin Books.

Thompson, Peter, Macklin, Robert 2004. The Man Who Died Twice Allen and Unwin. Crows Nest.

Tiffen, Rodney. 1978. The News from South East Asia: The Sociology of Newsmaking. Singapore. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.